7

Lumen Learning and Dr. Senta German

In this chapter

Cycladic Art

The Cyclades are a group of Greek islands in the Aegean Sea that encircle the island of Delos. The islands were known for their white marble, mined during the Greek Bronze Age and throughout Classical history.

Their geographical location placed them, like the island of Crete, in the center of trade between Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor, and the Near East. The indigenous civilization on the Cyclades reached its high point during the Bronze Age. The islands were later occupied by the Minoans, Mycenaeans, and later the Greeks.

Cycladic Sculptures

Cycladic art is best known for its small-scale, marble figurines. From the late fourth millennium BCE to the early second millennium BCE, Cycladic sculptures went through a series of stylistic shifts, with their bodily forms varying from geometric to organic. The purpose of these figurines is unknown, although all that have been discovered were located in graves. While it is clear that they were regularly used in funerary practices, their precise function remains a mystery.

Some are found in graves completely intact, others are found broken into pieces, others show signs of being used during the lifetime of the deceased, but some graves do not contain the figurines. Furthermore, the figurines were buried equally between men and women. The male and female forms do not seem to be identified with a specific gender during burial. These figures are based in simple geometric shapes.

Cycladic Female Figures

The abstract female figures all follow the same mold. Each is a carved statuette of a nude woman with her arms crossed over her abdomen. The bodies are roughly triangular and the feet are kept together. The head of the women is an inverted triangle with a rounded chin and the nose of the figurine protrudes from the center.

Each figure has modeled breasts, and incised lines draw attention to the pubic region with a triangle. The swollen bellies on some figurines might indicate pregnancy or symbolic fertility. The incised lines also provide small details, such as toes on the feet, and to delineate the arms from each other and the stomach.

Their flat back and inability to stand on their carved feet suggest that these figures were meant to lie down. While today they are featureless and remain the stark white of the marble, traces of paint allow us to know that they were once colored. Paint would have been applied on the face to demarcate the eyes, mouth, and hair. Dots were used to decorate the figures with bracelets and necklaces.

Cycladic Male Figures

Male figures are also found in Cycladic grave sites. These figures differ from the females, as the male typically sits on a chair and plays a musical instrument, such as the pipes or a harp. Harp players, like the one in the example below, play the frame harp, a Near Eastern ancestor of the modern harp.

The figures, their chairs, and instruments are all carved into elegant, cylindrical shapes. Like the female figures, the shape of the male figure is reliant on geometric shapes and flat planes. The incised lines provide details (such as toes), and paint added distinctive features to the now-blank faces.

Other Cycladic Figures

While reclining female and seated male figurines are the most common Cycladic sculptures discovered, other forms were produced, such as animals and abstracted humanoid forms. Examples include the terra cotta figurines of bovine animals (possibly oxen or bulls) that date to 2200–2000 BCE, and small, flat sculptures that resemble female figures shaped like violins; these date to the Grotta–Pelos culture , also known as Early Cycladic I (c. 3300–2700 BCE). Like other Cycladic sculptures discovered to date, the purposes of these figurines remain unknown.

Minoan Art: The Palace at Knossos (Crete)

Restoration versus conservation

What happens to an archaeological site after the archaeologist’s work is completed? Should the site (or parts of it) be restored to what we believe (based on evidence) it once looked like? Or should the site be protected through conservation and left as is? A visit to an unrestored archaeological site can be uninspiring—even the most lavish ancient sites can appear to be piles of unorganized stones framed by broken columns and other fragments. And while modern conservation principles insist on the reversibility of any treatment (in case better treatments are discovered in the future), in the past, conservators didn’t have the resources or science that is available today.

Knossos

The archaeological site of Knossos (on the island of Crete) —traditionally called a palace—is the second most popular tourist attraction in all of Greece (after the Acropolis in Athens), hosting hundreds of thousands of tourists a year. But its primary attraction is not so much the authentic Bronze Age remains (which are more than three thousand years old) but rather the extensive early 20th century restorations installed by the site’s excavator, Sir Arthur Evans, in the early twentieth century.

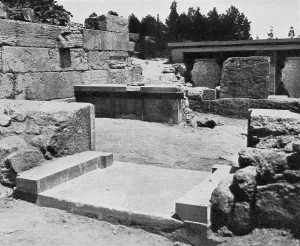

Archaeological restorations offer important information about the history of a site and Knossos doesn’t disappoint—one can see the earliest throne room in Europe, walk through the monumental Northern entrance to the palace, marvel at colorful wall paintings and enjoy the elegance of a queen’s apartments. All these spaces, however, are the result of extensive, contentious and, in some cases, damaging restoration. Knossos asks us to consider how we can preserve an archaeological site, while at the same time providing a valuable, educational experience for visitors that nonetheless remains true to the remains.

Considering Evans’ reconstructions

The Evans restoration at Knossos are important for several reasons:

- If Evans hadn’t worked to preserve and restore so much of Knossos beginning in 1901, it would have undoubtedly been largely lost.

- The restoration of the site undertaken by Evans, with its elegantly painted Throne Room (below) makes very real our historical understanding, originally revealed by Homer, of the power and prestige of the kings of Crete.

- The beautiful, although sometimes inaccurate, restorations of architecture and wall paintings by Evans evoke the elegance and skill of Minoan architects and painters.

These are the undeniable benefits of Evans’s restorations and among the aspects of a visit to Knossos that everyone values. It is the smooth corniced walls, bright paintings, and whole passages stepped with balustrades at Knossos that the post cards, camera snaps, and human memory preserve, and that has translated into important support for the site—intellectually, politically, and financially.

At the same time, the Evans restorations are problematic. In some cases, what is restored does not accurately reflect what was found. Instead, a grander, and more complete, experience is presented. For example, when you visit Knossos, because of the way it is reconstructed, it is very easy to believe that all that was ever found there was a Late Bronze Age palace.

Evans’s restoration of the Throne Room (and much else at the site) privileges the Late Bronze Age period of its history. The typical visitor likely won’t grasp that the Throne Room dates to the latest phase of Knossos—the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., though the site was occupied nearly continuously from the Neolithic to the Roman era (from the 8th millennium B.C.E. to at least the 5th century C.E.).

The power of Evans’s interpretation and reconstruction of the site as purely Minoan—the product of the indigenous culture of that island—is very much still with us despite the fact that much has changed about how art historians and archaeologists understand the different periods of construction at Knossos. Today, much of its final plan and form, which Evans reconstructed (including the Throne Room and most of the frescos), are understood as being of Mycenaean construction (not Minoan). Although this information is noted in texts mounted at the site, it is too often overlooked by visitors.

What is archaeological restoration?

When archaeological remains are revealed through excavation, they are often delicate and cannot survive long unprotected. Some archaeologists backfill their trenches (refill the excavated holes with the material that was removed) to help preserve remains. In other instances, architecture, graves, or the impressions left from ephemeral building materials (such as wood) are sometimes left exposed, and when this happens some sort of conservation should occur. By definition, any sort of conservation is restoration when the modern materials are layered on the ancient and made to look harmonious in form, color and/or texture. As a result, restorations are sometimes nearly indistinguishable from authentic materials, and this is where things get tricky—such as the situation at Knossos.

Before making an archaeological restoration, three essential issues must be examined:

- What specific point in a site or monument’s history will be the subject of the restoration? Many (most!) archaeological sites reflect a long occupation or use, and within that timeframe things change, are repaired, or rebuilt. What era of the site will be privileged by the restoration—and in turn, which eras of the site’s history will become harder to see and understand?

- How will future changes in the interpretation and knowledge about a site or monument be accommodated by restorations? Archaeological interpretations of sites evolve all the time, often through new discoveries elsewhere. Restorations, in order to remain accurate, need to take into account potential new scholarship that can change the history or meaning of a site or monument.

- Lastly and most importantly, restorations must be non-destructive and reversible. The first role of restoration is conservation. Therefore, the original remains must be entirely safe and not harmed in any way by restoration methods and materials. The reversibility of restorations not only has to do with the accommodation of changes in interpretation made above, but also with the need to leave the way open for less invasive, more gentle restoration methods in the future.

Restoration at Knossos

Aside from some gaps (for instance, during the First World War) Evans excavated at the site of Knossos each year from 1900 to 1930. Restoration of the architectural finds began almost immediately and can be divided into three phases, each characterized by the architect Evans hired to do the work. These three men, Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, and Piet De Jong, each had very different restoration philosophies.

Phase 1: Theodore Fyfe

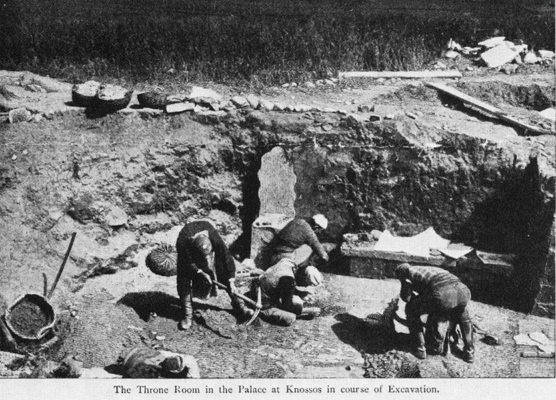

From 1901 to 1904, a young architect by the name of Theodore Fyfe was charged with the restorations at Knossos. It is likely that Evans hired him because the winter of 1900/01 had damaged the newly exposed Throne Room—the most important space excavated during that first season at the site.

Fyfe’s work at Knossos can be characterized by two things. First of all, he was devoted to the concept of minimal intervention. Second, when intervention was necessary, he made great efforts to use materials authentic to the Bronze Age structure (wood, limestone, rubble masonry) and even to use Bronze Age construction techniques, which he was able to glean from his onsite work. Clearly Fyfe was highly concerned about the truthfulness of his interventions and reconstructions; the only exception to this was his construction of modern-style pitched roofs to protect the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes.

Phase 2: Christian Doll

The second phase of restoration work at Knossos dates from 1905 to 1910, and was directed by Christian Doll. The first conservation work to which Doll had to attend to in 1905 was that of Fyfe’s. Essentially, Fyfe’s zeal to use authentic materials resulted in failure: he neglected in many cases to treat timbers before their use and he tended to use softwoods rather than hardwoods (all of which lead to rot). Also, rain was a destructive force in the winters, especially when it ran through newly exposed parts of the site. Doll’s first and most important project was to stabilize and reconstruct the Grand Staircase to its original four story height. This was an extremely difficult job as the exact nature of the ancient design eluded both him and Fyfe, so a certain amount of improvisation was needed. And, because the weight of the structure was so great, Doll used iron girders (imported from England at great expense) covered in cement to make them look like ancient wooden beams.

Doll’s approach to conservation was still anchored in preserving the excavated remains. However, Doll was no fan of the authentic materials used by Fyfe, as he saw how they had failed to preserve the many areas where they had been employed. Instead, Doll constructed structural systems based on techniques used in London at the time. Moreover, he employed contemporary architectural materials, such as the iron girders mentioned above, as well as concrete (the first use of this material at Knossos).

Phase 3: Piet De Jong

The third phase of conservation work was executed over a longer period of time, from 1922 to 1952, by Piet De Jong. The vast majority of what Knossos looks like today, with large passages of reconstructed walls and rooms, is his work.

Three main elements characterize De Jong’s work at Knossos. The most prominent was his use of iron reinforced concrete. In the twelve years between Doll’s and De Jong’s work, the use of reinforced concrete had grown in popularity because of its speedy construction, its relative cheapness, and its ability to be molded into nearly any shape. It was also thought to be nearly indestructible.

Another essential characteristic of De Jong’s work at Knossos was his use of reinforced concrete to construct parts of the palace beyond what had been found—some passages were based on archaeological evidence, some were not (the bases of these reconstructions came from Evans himself).

De Jong often did not merely end walls at the height of their discovery but would either finish them off with a flat roof and cornice, often decorated with double white horns (what some contemporary wall paintings of Bronze Age houses looked like), or would leave the top edge of walls with irregular stones, evoking a picturesque, antique view. When a complete vision of ancient Knossos could not be reconstituted, a romantic one was built instead.

The reconstruction of the interior decoration of the throne room was executed during this period and similarly exhibits a combination of the truthful reflection of archaeological remains and Evans’s creativity.

Lastly, an important characteristic of De Jong’s restorations was the placement of reproductions of wall paintings around his newly built spaces. Some paintings were placed very close to their findspots and therefore aimed at a more authentic reconstruction, while other paintings were reconstructed at some distance from where they had been discovered.

The question remains: why did Evans encourage De Jong’s radical approach to conservation, especially after two more conservative predecessors? Several reasons are at play, no doubt. The first, and possibly the most important, is the condition of Knossos after almost eight years of abandonment during the First World War. Aside from the wild overgrowth of weeds, there was much weather-related and other damage. However, the parts of the site that had been roofed (such as the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes) and sections that were more intact (such as the Grand Staircase), were in excellent shape and this no doubt convinced Evans of the importance of aggressive conservation work. Second, the iron-reinforced concrete which De Jong proposed to use was inexpensive and could be employed quickly. Third, Evans, in a masterful anticipation of the desires of future tourism, aimed to make a site that would vividly conjure the culture he had discovered, as much evocative and picturesque as historically accurate.

Conservation at Knossos after Evans

It is only fair to reflect upon the restorations of Knossos within their historical framework. The aims, methods, and materials used in restoration at the site over a period of some sixty years changed, reflecting a long list of crises, constraints, theories, and desires. Perhaps most significant, however, was Evans’s overriding conviction that the conservation of Knossos was an obligation born out of its great antiquity and unique importance. He knew this from his own Edwardian education, British colonial outlook, and his twenty-four year directorship of the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. Evans was keenly aware of how intimately connected the teaching of Knossos’s history was with how it was presented on site. He made Knossos into a museum and a showcase for the newly discovered Aegean Bronze Age chapter of ancient history and the earliest example of cultural tourism, today a mainstay of public historical education—not to mention local economies. Evans did it first at Knossos.

Conservation at Knossos has continued since De Jong’s work, although with new challenges. The most recent conservation work on the site has been focused largely on repairing Evans’s reconstructions. Despite a belief that reinforced concrete would last indefinitely, it has proven to be susceptible to the wet Cretan winters, crumbling and allowing for rust on the interior ironwork. In other areas the reinforced concrete proved to be structurally unsound.

In addition, the steady increase of tourist traffic since the 1950s has meant growing stress on both the original architecture of Knossos as well as its reconstructions. Sustained foot fall, increasing weight load as well as touching and sitting, is increasingly destructive. To combat this, the Greek Archaeological Service, under the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, has closed off large sections of Knossos and generally restricted circulation on the site. In the 1990s it conducted extensive conservation of both ancient and modern structures as well as building new corrugated plastic roofing. At present the Service is working on a visitor management plan for the site and the Greek government has applied to UNESCO for World Heritage Status for Knossos as well as four other Minoan palatial sites which would afford much needed support for ongoing conservation efforts.

Bull-leaping fresco from the palace of Knossos

Taking the bull by the horns

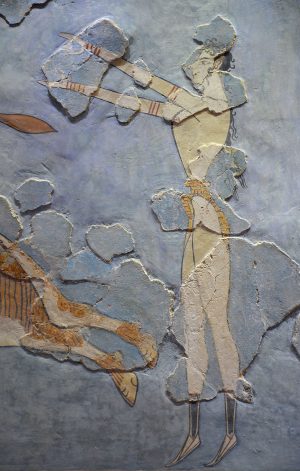

Bull sports—including leaping over them, fighting them, running from them, or riding them—have been practiced all around the globe for millennia. Perhaps the best-loved ancient illustration of this, called the bull-leaping or Toreador fresco, comes from the site of Knossos on the island of Crete. The wall painting, as it is now reconstructed, shows three people leaping over a bull: one person at its front, another over its back, and a third at its rear.

The image is a composite of at least seven panels, each .78 meters (about 2.5 feet) high. Fragments of this extensive wall painting were found very badly damaged in the fill above the walls in the Court of the Stone Spout, on the east side of the Central Court at Knossos. The fact that the paintings were found in fill indicates that this wall painting was destroyed as part of a renovation. The pottery which was found together with the fragments gives us its date, likely LM II(around 1400 B.C.E.).

Reconstructed but still incomplete

When Sir Arthur Evans, the first archaeologist to work at Knossos, found the fragments, he recognized them as illustrating an early example of bull sports, and he was eager to create a complete image that he could share with the world. He hired a well-known archaeological restorer, Émile Gilliéron, to create the image we know today from the largest bits of the seven panels. Unfortunately, it is impossible to reconstruct all of the original panels and to get a sense of the painting at all, we are left with Gilliéron’s reconstruction.

Visual gymnastics

What we see is a freeze-frame of a very fast moving scene. The central image of the fresco as reconstructed is a bull charging with such force that its front and back legs are in midair. In front of the bull is a person grasping its horns, seemingly about to vault over it. The next person is in mid-vault, upside down, over the back of the bull, and the final person is facing the rear of the animal, arms out, apparently just having dismounted—“sticking the landing,” as they say in gymnastics.

The people on either side of the bull, as reconstructed, bear markers of both male and female gender: they are painted white, which indicates a female figure according to ancient Egyptian gender-color conventions, which we know the Minoans also used. But both characters wear merely a loincloth, which is male dress. The hairstyle (curls at the top with locks falling down the back) is not uncommon in representations of both youthful males and females. Many interpretations of this gender crossing are possible, but there is little evidence to support one over another, unfortunately. At the very least, we can say that the representation of gender in the Late Aegean Bronze Age was fluid.

The person at the center of the action, vaulting over the bull’s back, is painted brown, which indicates male gender according to ancient Egyptian gender-color conventions, and this makes sense considering his loincloth. It is interesting to note that the muscles of all three of the bull leapers, at their thighs and chests, have been very delicately articulated, accentuating their athletic build.

The background of the scene is blue, white, or yellow monochrome, and indicate no architectural context for the activity. Moreover, the seven panels and Gilliéron’s composite reconstruction all show a border of painted richly variegated stones overlapping in patches. So, it seems we are meant to see these scenes as abstracted action within frames, not part of a wider visual field or narrative.

A rite of passage?

The most interesting question about the bull leaping paintings from Knossos is what they might mean. We cannot understand the whole bull-leaping cycle in detail as it is so fragmentary, but we know that it covered a lot of wall space and a considerable amount of resources must have been expended to create it.

As mentioned above, many cultures across space and time have engaged in bull sports, and they all have a few things in common. First, these sports are life-threatening. To race, dance with, leap over, or kill a bull might very well get you killed. Second, these activities are usually performed before a crowd: they are a civic event, publicly presented and recorded in memory. Third, those who participate in these bull activities are often youths at an age when they are passing from childhood into adulthood and the achievement of the bull sport contributes to that passage. Anthropologists refer this sort of activity as a “rite of passage,” which, when witnessed by one’s community, establishes the participant as an adult.

Therefore, we might surmise that the bull leaping scenes from Knossos refer to such a rite of passage ceremony. Many have identified the Central Court (Theatral area) just beyond the west façade of the palace at Knossos as locations where bull-leaping ceremonies might have taken place. We may never know the exact meaning of these paintings, but they continue to resonate with us today—not only because of their beauty and dynamism, but because they represent an activity that is still an important part of many cultures around the world.

Minoan Woman or Goddess from the Palace of Knossos (“La Parisienne”)

“Parisian” from ancient Crete

This image of a young woman with a bright dress and curly hair is among the best known images in Minoan art. It is also one of the few representations of Minoan people rendered in color and detail, and it is a beautiful example of Minoan wall painting. Shortly after it was first discovered by Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos, it was seen by Edmond Pottier, a famous art historian of Greek pottery, who likened her charming look to the contemporary women of Paris. She has been known as “La Parisienne” ever since.

The sacred knot

Only La Parisienne’s head and upper body are preserved. Her hair is black and curly, with one curl springing down onto her forehead and others cascading down her neck and upper back. Her skin is white, which is in imitation of the ancient Egyptian color convention (women painted white, men brown), and her large, darkly outlined eye also reminds us of Egyptian style, but her bright red lips are unique. She wears an elaborately woven blue and red striped dress, with a blue banded edge attached with red flecked loops. Tied to the back of the dress is a “sacred knot,” as Evans first called it. This is a loop of long cloth tied with another loop at the nape of the neck, leaving a length of the cloth trailing down the back.

This is one of only two representations of a woman actually wearing a sacred knot, although the knots themselves are found on seals, painted on pottery, in other frescos, and rendered in ivory or faience. This knot is thought to designate the wearer as a holy person, so this Minoan woman may be a priestess.

Found in fragments

The wall painting of which La Parisienne is a part was discovered heavily damaged and fallen from an upper story in the western wing of Knossos. It was painted in buon fresco (on wet plaster) as most Minoan wall paintings were, and given its archaeological context is likely one of the last painted works of the palace, dating to LM III (around 1350 B.C.E.). Specifically, this fragment was part of a two tiered scene that is about a half-meter (about 1.5 feet) wide, called the Camp Stool fresco (shown below as a reconstruction). Featured on both the top and bottom panels are pairs of men and women in profile sitting and standing and holding up elegant vessels. La Parisienne comes from one of the female pairs.

It has been suggested that the part of the palace of Knossos from which this painted scene fell was used for ceremonies and feasting; if this is true, subject matter depicting toasts being made would fit in nicely. Whatever her original meaning, La Parisienne is an enduring testament to the skill of Minoan fresco painters.

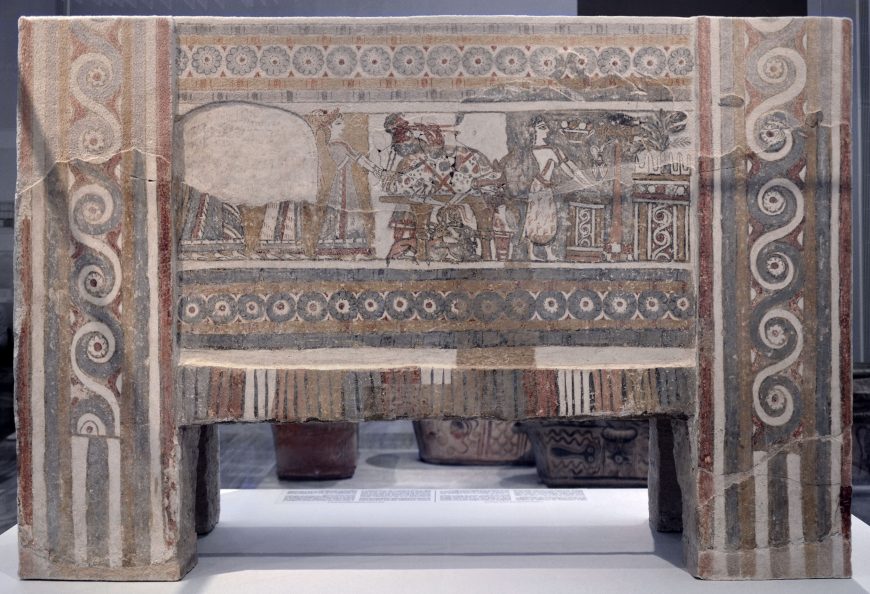

Hagia Triada Sacrophagus

A coffin for royalty?

Many images of Minoan rituals are fragmentary and therefore difficult to interpret. There are very few complete, narrative-style representations of religious topics, and the Hagia Triada (also sometimes spelled “Agia Triada”) is the best among them. This sarcophagus was found in 1903 by the Italian archaeologist Roberto Paribeni in Tomb 4 of the hilltop cemetery north of the site of Hagia Triada, a large and wealthy ancient Minoan settlement in south central Crete. Tomb 4 was a family tomb containing the sarcophagus, constructed of limestone, and another large ceramic coffin. The tomb was disturbed in antiquity, but some small burial goods were left behind by the looters: a carved stone bowl, a triton shell, and a fragment of a female terracotta figurine. These remaining grave goods and the elaborate nature of the Hagia Triada sarcophagus has led to the identification of Tomb 4 as that of royalty.

A story in fresco

The Hagia Triada sarcophagus is the only Minoan sarcophagus known to be entirely painted. It was created using fresco, like contemporaneous wall painting, and illustrates a complex narrative scene, apparently of burial and sacrifice. The object itself is substantial, measuring 1.375 meters (about 4.5 feet) long, .45 meters (about 1.5 feet) wide and .985 meters (about 3 feet) high.

One of the long sides is the most complete and shows a funeral procession of offering bearers and a libation ceremony that features seven figures—two women and five men. From the far left, we see a female in profile facing left, dressed in an elaborate hide skirt and open short-sleeved shirt, holding a vessel in both hands while pouring the contents into a larger vessel which is resting on a stone platform between two poles. The poles are set on richly-veined stone bases and are topped with double axes surmounted by birds. Behind the woman pouring is another woman, and behind her, a man. The second woman, who is elaborately robed and wears a crown of lilies, carries on her shoulders a pole that supports two vessels identical to the one being used for pouring by the first female. The man behind her plays a lyre and is also elaborately robed.

The next three people from the left are young men, each bare-chested and wearing a hide skirt. The first two hold bovine statues, one spotted brown, one black; the third man holds a model of a boat. These three men are in composite profile, with shoulders frontal but legs and head in profile, a common Egyptian painting convention. They are also set against a blue background, which is different from the rest of the scene on this side of the sarcophagus. Another man faces these three. He has no feet and looks posed like a sculpture, and it is thought this represents the deceased person. He wears a long hide robe with gold trim.

Between the three men and the deceased is a set of three steps, perhaps an altar, which has some damage at the top. There is a tree above the altar, and it is possible (based on other images of similar altars) that it is supposed to be growing out from the altar itself. Behind the deceased is another structure, elaborately painted with running spirals and inlaid with veined stone. This is thought to be the tomb of the deceased.

Offerings and altars

On the opposite side of the sarcophagus, there are another seven figures—six female and one male. Beginning again from the left, we are met with a large patch of damage which only leaves the legs and feet of two pairs of women, all with elaborate long robes, moving to the right.

A fifth female figure, fully visible, leads them, also well-dressed and wearing a lily crown. She is in full profile, with yellow hair, her arms stretched down towards to the ground. She and the four women behind her are all set in a bright yellow background. Moving to the left, the background color changes to white and against this is a male double-flute player wearing a short blue robe and long curls. He stands behind an offering table on which lies a trussed bull on its side, facing the viewer. Red streaks of blood can be seen coming from the bull’s neck and pouring into a vessel that sits at the foot of the table. Beneath the table are two small goats, possibly awaiting a similar fate.

To the right of this large altar the background color changes to blue; a woman stands before another low altar wearing a hide skirt. This altar is decorated with a red and white running spiral design and on top sits a shallow grey bowl, possibly silver, above which floats in the field a painted beaked pitcher and a two-handled bowl with what appears to be round fruit—possibly all offerings. To the right of this altar is another pole, this one set in a red and white checked base, with a double axe and bird at the top. Lastly, in the field is an architectural structure, also with red and white running spirals and four pairs of horns on top and from which grows a great green tree.

No surface left undecorated

One of the short sides of the Hagia Triada sarcophagus has two scenes situated one on top of the other, while the opposite short side has only one scene. On the side with two scenes, the top one is almost entirely lost from damage but enough remains to indicate a procession of men in short pointed kilts of richly woven textiles. Beneath this scene is a horse-drawn chariot with an ox-hide carriage in which two women ride, both dressed in elaborate robes and one holding a whip.

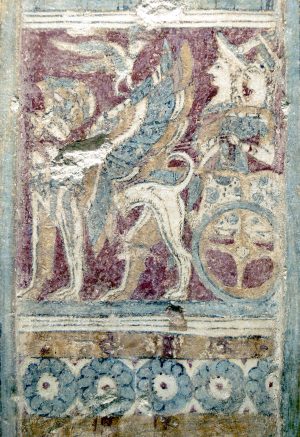

On the other short side there is a griffin–drawn chariot with another pair of women riding in an ox-hide carriage also richly dressed and wearing pointed hats. The griffins are multicolored and spread their wings, as if in flight; above them flies a bird in profile, moving in the opposite direction.

Surrounding all five of these scenes on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus are framing elements: rows of rosettes, bands of colors to imitate richly veined stone, running spirals with central rosettes, and colorful striped bands. It is colorfully painted from top to bottom.

Simple story, complex questions

In some ways what we see on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus is simple to understand: women and men in elite dress are busy making sacrifices and preparing the deceased for burial before his tomb. However, looking more deeply, many questions remain. How is it to be read? Is there a prescribed order to the images? What does the change in background color mean? Who exactly are these people—are they all priestesses and priests? Are they mythological characters? Who was the deceased? Was this a special sort of burial, or did everybody get this treatment? These are questions that have yet to be answered with confidence.

Octopus Vase

Ceramics for the wealthy

One of the most important aspects of Minoan culture was its ceramics. Pottery today may not seem particularly interesting or important, but in the second millennium B.C.E., it was a high art form and its manufacture was often closely associated with centers of power. Much like the production of porcelain for European royal houses in the 18th century, the production of pottery on Crete tells us about elite tastes, how the powerful met and shared meals, and with whom they traded.

This vase, found at Palaikastro, a wealthy site on the far eastern coast of Crete, is the perfect example of elite Minoan ceramic manufacture. It is 27 cm (about 10.5 inches) high, wheel-made, hand-painted, and meant to hold a valuable liquid—perhaps oil of some kind. Its shape is somewhat unusual, constructed by slipping together, while still leather hard (clay that is not quite dry), two shallow plates which had been made on a fast spinning potter’s wheel and with highly refined clay. The circular bases of these shallow plates are still visible in the center of both sides of the flask. A spout and stirrup-style handles (which would allow the user to carefully control the flow of the liquid out of the container) were added by hand, as well as a base, to facilitate the standing upright of the vessel.

Inspired by the sea

Lastly, the Marine Style decoration would have been added. Using dark slip on the surface of the clay, the Minoan painter of this vessel filled the center with a charming octopus, swimming diagonally, with tentacles extended out to the full perimeter of the flask and wide eyes that stare out at the viewer with an almost cartoon-like friendliness. Around this creature’s limbs we find sea urchins, coral, and triton shells; no empty space is left unfilled, lending a sense of writhing energy to the overall composition.

Marine-Style pottery, of which this vessel is a prime example, is regarded as the pinnacle of Minoan palatial pottery production, specifically of the LM I period (around 1400 B.C.E.). Those who believe “hands” (that is, specific artists) can be identified in the painting of Bronze Age pottery have identified this vessel as the work of the Marine Style Master, who worked at the site of Palaikastro. The era of Marine Style pottery coincided with a period during which the Minoans’ trade networks spanned widely across the Mediterranean, from Crete to Cyprus, the Levant, mainland Greece, and Egypt. Some have connected this seafaring skill to the popularity of Marine Style pottery. The style was imitated by potters on the Greek mainland as well as the islands of Melos, and Aegina, but none could match the charm and grace of the Minoan inventors of the style.

Snake Goddess

An enticing mystery

It has been said that the image of the Snake Goddess, discovered by Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos on Crete, is one of the most frequently reproduced sculptures from antiquity. Whether or not this is true, it is certainly the case that she is a powerful and evocative image. What she meant to the Minoans who made her, however, is not very well understood.

The “Temple Repositories”

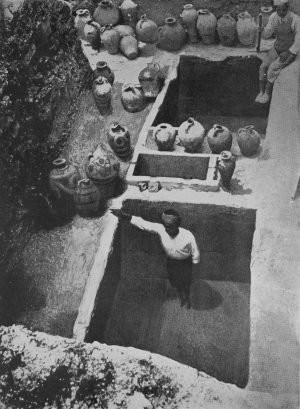

Evans found the sculpture of the Snake Goddess in a secondary exploration of the complex he called a “palace” at Knossos. After digging out the entire western wing, he decided to check under the paving stones. Most covered nothing but earth, but just south of the Throne Room, he discovered two stone-lined pits containing a wide variety of precious things, mostly broken: scraps of gold, ivory, faience (the largest deposit of faience on Crete), stone inlay, unworked horn, ceramic vessels, seal stones, sealings, shells, the vertebrae of large fish, and the broken pieces of at least three figurines, of which the Snake Goddess was one.

Because of the fragmentary nature of these valuable objects, Evans assumed what he had found were damaged pieces that had been cleaned out from a temple. He named the pits the “Temple Repositories” and immediately set upon the reconstruction of as much as he could, with special interest in the figurines, which he assumed were of goddesses.

The hat and the cat

The Snake Goddess, as originally excavated, lacked a head and half of her left arm. The complete right arm held a short wavy striped stick, which Evans interpreted as a snake. This was, in some measure, to match the other nearly complete figurine found in the Temple Repositories, which clearly had snakes slithering up both of her arms. The restoration of the Snake Goddess was done by the Danish artist Halvor Bagge together with Evans. Their contribution to the figurine was the creation of a matching arm and stripy snake, the head of the goddess, and the placement of the hat and cat (separate faience pieces found in the Temple Repositories) on her head.

In her restored state, the Snake Goddess is 29.5 cm (about 11.5 inches) high, a youthful woman wearing a full skirt made of seven flounced layers of multicolored cloth. This is likely not a representation of striped cloth, but rather flounces made from multiple colorful bands of cloth, the weaving of which was a Minoan specialty. Over the skirt she wears a front and back apron decorated with a geometric diamond design. The top of the skirt and apron has a wide, vertically-striped band that wraps tightly around the figure’s waist. On top, she wears a short-sleeved, striped shirt tied with an elaborate knot at the waist, with a low-cut front that exposes her large, bare breasts. The Snake Goddess’s head, restored by Bagge and Evans, stares straight forward, topped by the spherical object that Bagge and Evans believed would make a good crown, and, finally, a small sitting cat. Her long black hair hangs down her back and curls down around her breasts.

Really a goddess?

The Snake Goddess is a provocative image, but its restoration and interpretation are problematic. The crown and cat have no parallel in any image of a Bronze Age woman, so these should be discounted. The interpretation of this figure as a goddess is also difficult, since there is no evidence of what a Minoan goddess might have looked like. Many images of elite Minoan women, perhaps priestesses, look very much like this figurine. If it is the action of snake-wrangling that makes her a goddess, this is also a problem. The image of a woman taming one or more snakes is entirely unique to the Temple Repositories. Therefore, If she is a snake goddess, she is not a particularly popular one.

Certainly, Evans was interested in finding a goddess at Knossos. Even before he excavated at the site, he had argued that there was a great mother goddess who was worshiped in the pre-Classical Greek world. With the Snake Goddess, Evans found—or fashioned—what he had anticipated. Its authenticity and meaning, however, leave many questions today.

Harvester Vase

Small but powerful

Found at Hagia Triada, an elite site associated with Minoan palaces and dating to the Neopalatial period, (1600-1450 B.C.E.) the Harvester Vase displays a detailed and fascinating scene of men marching and singing in what appears to be a harvest celebration. Although it is not a grand artistic monument, this small vessel (about 4.5 inches in diameter), communicates a grace and vitality typical of Aegean Bronze Age art.

Imitating an eggshell

The Harvester Vase is actually not a vase but rather a rhyton, a ritual vessel used for pouring liquids. It has a hole at the top and would have had a hole at the bottom before it was damaged. It is made of black steatiteand is shaped to look like a similar vessel made of an even more valuable material: an ostrich egg shell. Ostrich egg rhyta were some of the most luxurious and exotic ritual goods in the Aegean Bronze Age. This type of object was made by drilling holes at either end of an ostrich egg (imported from Egypt), drawing out the contents, and affixing a decorative rim on the top and at the bottom. However, what the Harvester Vase lacks in imported luxury, it makes up for in sheer sculptural power.

A rhythmic procession

The miniature scene, carved in relief, illustrates some twenty-seven men in a procession. Most of these men are depicted in pairs, legs stepping high and right arms bent at the elbow, hands held close to the chest, and wearing identical costumes: loincloths, flat caps, carrying bags or pads on the left thigh, and on the left shoulder, a pole with a short curved blade and a three pronged fork. These men are all young, slim, and muscular, with angular faces turned up to the sky. Their paired, lock-step procession evokes marching or rhythmic movement. There is one exception to this rhythm: near the back of the group, one man turns to look behind him, perhaps because, it would appear, another has fallen just at his back.

This marching group is led by an apparently older man, wearing long shaggy hair and a fringed robe with a scallop pattern (above). He carries a long staff, crooked at the bottom and tapering at the top. In the middle of the group of men behind him is another single figure, a man who looks perhaps not as young and lean as those in the group, who is shaking a sistrum (a musical instrument used in religious rituals). These were common in ancient Egypt as well as in ancient Greece and Rome; examples have been found on Bronze Age Crete as well. This man appears to be shouting or singing with his mouth wide open and he is followed close behind by a rank of four men who also have wide open mouths and wear cloaks around their shoulders.

Reaping or sowing?

As the name of this vessel indicates, it is generally thought that its decoration refers to harvesting, the key evidence being the long implement each of the younger men is carrying over his shoulder. What is not clear is exactly what the implement is. If it is a winnowing fork, these men are harvesting, collecting mature cereal crops; they will use the fork to separate the grain from its husk. If the implement is a hoe, festooned with branches, then the men are off to plant seeds—perhaps to be found in each of the men’s bags. Which it is—harvesting or planting—we may never know, but what is clear is the masculine, communal, and celebratory nature of the activity depicted on this beautiful vessel.

Mycenaean Art & Architecture

Mycenaean Architecture

Mycenaean culture can be summarized by its architecture, whose remains demonstrate the Mycenaeans’ war-like culture and the dominance of citadel sites ruled by a single ruler. The Mycenaeans populated Greece and built citadels on high, rocky outcroppings that provided natural fortification and overlooked the plains used for farming and raising livestock. The citadels vary from city to city but each share common attributes, including building techniques and architectural features.

Building Techniques

The walls of Mycenaean citadel sites were often built with ashlar and massive stone blocks. The blocks were considered too large to be moved by humans and were believed by ancient Greeks to have been erected by the Cyclopes—one-eyed giants. Due to this ancient belief, the use of large, roughly cut, ashlar blocks in building is referred to as Cyclopean masonry. The thick Cyclopean walls reflect a need for protection and self-defense since these walls often encircled the citadel site and the acropolis on which the site was located.

Corbel Arch

The Mycenaeans also relied on new techniques of building to create supportive archways and vaults. A typical post and lintel structure is not strong enough to support the heavy structures built above it. Therefore, a corbeled (or corbel) arch is employed over doorways to relieve the weight on the lintel.

The corbel arch is constructed by offsetting successive courses of stone (or brick) at the springline of the walls so that they project towards the archway’s center from each supporting side, until the courses meet at the apex of the archway (often, the last gap is bridged with a flat stone). The corbel arch was often used by the Mycenaeans in conjunction with a relieving triangle, which was a triangular block of stone that fit into the recess of the corbeled arch and helped to redistribute weight from the lintel to the supporting walls.

Citadel Sites

Mycenaean citadel sites were centered around the megaron, a reception area for the king. The megaron was a rectangular hall, fronted by an open, two-columned porch. It contained a more or less central open hearth, which was vented though an oculus in the roof above it and surrounded by four columns. The architectural plan of the megaron became the basic shape of Greek temples, demonstrating the cultural shift as the gods of ancient Greece took the place of the Mycenaean rulers.

Citadel sites were protected from invasion through natural and man-made fortification. In addition to thick walls, the sites were protected by controlled access. Entrance to the site was through one or two large gates, and the pathway into the main part of the citadel was often controlled by more gates or narrow passageways. Since citadels had to protect the area’s people in times of warfare, the sites were equipped for sieges. Deep water wells, storage rooms, and open space for livestock and additional citizens allowed a city to access basic needs while being protected during times of war.

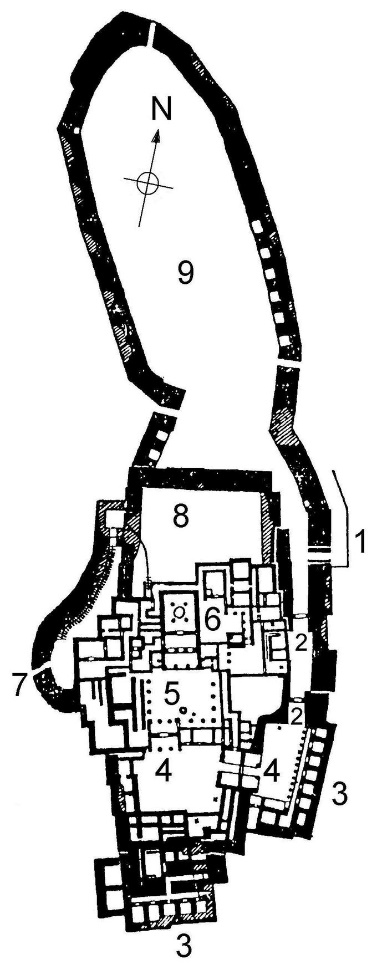

Mycenae

The citadel site of Mycenae was the center of Mycenaean culture. It overlooks the Argos plain on the Peloponnesian peninsula, and according to Greek mythology was the home to King Agamemnon.

The site’s megaron sits on the highest part of the acropolis and is reached through a large staircase. Inside the walls are various rooms for administration and storage along with palace quarters, living spaces, and temples. A large grave site, known as Grave Circle A, is also built within the walls.

The main approach to the citadel is through

the Lion Gate, a cyclopean-walled entrance way. The gate is 20 feet wide, which is large enough for citizens and wagons to pass through, but its size and the walls on either side create a tunneling effect that makes it difficult for an invading army to penetrate.

The gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel. The Lion Gate received its name from its decorated relieving triangle of lions one either side of a single column. This composition of lions or another feline animal flanking a single object is known as a heraldic composition. The lions represent cultural influences from the Ancient Near East. Their heads are turned to face outwards and confront those who enter the gate.

The gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel. The Lion Gate received its name from its decorated relieving triangle of lions one either side of a single column. This composition of lions or another feline animal flanking a single object is known as a heraldic composition. The lions represent cultural influences from the Ancient Near East. Their heads are turned to face outwards and confront those who enter the gate.

Mycenae is also home to a subterranean beehive-shaped tomb (also known as a tholos tomb) that was located outside the citadel walls. The tomb is known today as the Treasury of Atreus, due to the wealth of grave goods found there.

This tomb and others like it are demonstrations of corbeled vaulting that covers an expansive open space. The vault is 44 feet high and 48 feet in diameter. The tombs are entered through a narrow passageway known as a dromos and a post-and-lintel doorway topped by a relieving triangle.

Tiyrns

The citadel site of Tiryns, another example of Mycenaean fortification, was a hill fort that has been occupied over the course of 7000 years. It reached its height between 1400 and 1200 BCE, when it was one of the most important centers of the Mycenaean world. Its most notable features were its palace, its Cyclopean tunnels, its walls, and its tightly controlled access to the megaron and main rooms of the citadel.

Just a few gates provide access to the hill but only one path leads to the main site. This path is narrow and protected by a series of gates that could be opened and closed to trap invaders. The central megaron is easy to locate, and it is surrounded by various palatial and administrative rooms. The megaron is accessed through a courtyard that is decorated on three sides with a colonnade.

The famous megaron has a large reception hall, the main room of which had a throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. It was laid out around a circular hearth surrounded by four columns. Although individual citadel sites varied to a degree, their overall uniformity allows us to compare design elements easily. For example, the hearth of the megaron at the citadel of Pylos provides an idea of how its counterpart at Tiryns appears.

Mycenaean Metallurgy

The Mycenaeans were masterful metalworkers, as their gold, silver, and bronze daggers, drinking cups, and other objects demonstrate.

Grave Circle A at Mycenae

Grave Circle A is a set of graves from the sixteenth century BCE located at Mycenae. The grave circle was originally located outside the walls of the city but was later encompassed inside the walls of the citadel when the city’s walls were enlarged during the thirteenth century BCE. The grave circle is surrounded by a second wall and only has one entrance. Inside are six tombs for nineteen bodies that were buried inside shaft graves. The shaft graves were deep, narrow shafts dug into the ground. The body would be placed inside a stone coffin and placed at the bottom of the grave along with grave goods. The graves were often marked by a mound of earth above them and grave stele.

The grave site was excavated by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876, who excavated ancient sites such as Mycenae and Troy based on the writings of Homer and was determined to find archaeological remains that aligned with observations discussed in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The archaeological methods of the nineteenth century were different than those of the twenty-first century and Schliemann’s desire to discover remains that aligned with mythologies and Homeric stories did not seem as unusual as it does today. Upon excavating the tombs, Schliemann declared that he found the remains of Agamemnon and many of his followers.

Grave Circle B

An additional grave circle, Grave Circle B, is also located at Mycenae, although this one was never incorporated into the citadel site. The two grave circles were elite burial grounds for the ruling dynasty. The graves were filled with precious items made from expensive material, including gold, silver, and bronze.

The amount of gold, silver, and previous materials in these tombs not only depict the wealth of the ruling class of the Mycenae but also demonstrates the talent and artistry of Mycenaean metalworking. Reoccurring themes and motifs underline the culture’s propensity for war and the cross-cultural connections that the Mycenaeans established with other Mediterranean cultures through trade, including the Minoans, Egyptians, and even the Orientalizing style of the Ancient Near East

Gold Death Masks

Repoussé death masks were found in many of the tombs. The death masks were created from thin sheets of gold, through a careful method of metalworking to create a low relief.

These objects are fragile, carefully crafted, and laid over the face of the dead. Schliemann called the most famous of the death masks the Mask of Agamemnon, under the assumption that this was the burial site of the Homeric king. The mask depicts a man with a triangular face, bushy eyebrows, a narrow nose, pursed lips, a mustache, and stylized ears.

This mask is an impressive and beautiful specimen but looks quite different from other death masks found at the site. The faces on other death masks are rounder; the eyes are more bulbous; and at least one bears a hint of a smile. None of the other figures have a mustache or even the hint of beard.

In fact, the mustache looks distinctly nineteenth century and is comparable to the mustache that Schliemann himself had. The artistic quality between the Mask of Agamemnon and the others seems dramatically different. Despite these differences, the Mask of Agamemnon has inserted itself into the story of Mycenaean art.

Bronze Daggers

Decorative bronze daggers found in the grave shafts suggest there were multicultural influences on Mycenaean artists. These ceremonial daggers were made of bronze and inlaid in silver, gold, and niello with scenes that were clearly influenced from foreign cultures.

Two daggers that were excavated depict scenes of hunts, which suggest an Ancient Near East influence. One of these scenes depicts lions hunting prey, while the other scene depicts a lion hunt. The portrayal of the figures in the lion hunt scene draws distinctly from the style of figures found in Minoan painting. These figures have narrow waists, broad shoulders, and large, muscular thighs.

The scene between the hunters and the lions is dramatic and full of energy, another Minoan influence. Another dagger depicts the influence of Minoan painting and imagery through the depiction of marine life, and Egyptian influences are seen on a dagger filled with lotus and papyrus reeds along with fowl.

Gold and Silver Drinking Cups

A variety of gold and silver drinking cups have also been found in these grave shafts. These include a rhyton in the shape of a bull’s head, with golden horns and a decorative, stylized gold flower, made from silver repoussé. Other cups include the golden Cup of Nestor, a large two handle cup that Schliemann attributed to the legendary Mycenaean hero Nestor, a Trojan War veteran who plays a peripheral role in The Odyssey.

A silver rhyton called the Silver Siege Rhyton was likely used for ritual libations. The Silver Siege Rhyton is unique for its depiction of a siege. The scene is only preserved on a portion of the rhyton, but a landscape of trees and a fortress wall are clearly recognizable. The figures in the scene appear to be in various positions, some men fight each other. An archer crouches with his bow and arrow, while others throw rocks down from the wall at the invaders.

A third rhyton in the form of a bull’s head suggests a similarity with the Minoan culture, like the dagger mentioned earlier. The rhyton consists primarily of silver with gold-leaf accents. Its purpose as a ceremonial vessel arguably places the bull in a role of significance in the Mycenaean culture.

Mycenaean Ceramics

The Mycenaeans created numerous ceramic vessels of various types and decorated them in a variety of styles . These vessels were popular outside of Greece, and were often exported and traded around the Mediterranean and have been found in Egypt, Italy, Asia Minor, and Spain.

Two of the main production centers were the Mycenaean cities at Athens and Corinth. The products of the two centers were distinguishable by their color and decoration. Corinthian clay was a pale yellow and tended to feature painted scenes based on nature, while the Athenian potters decorated their vessels with a rich red and preferred geometric designs.

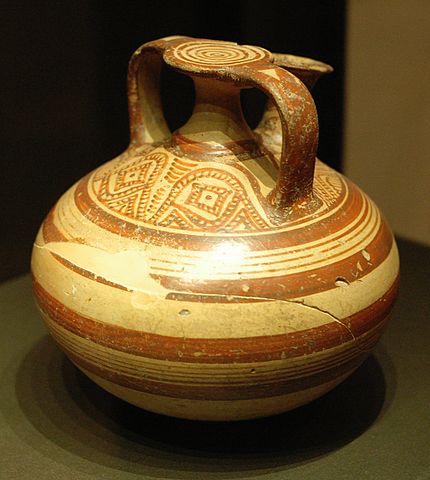

Vessels

The most popular types of vessels included kraters —large, open-mouth jars to mix wine and water—pitchers, and stirrup jars, which are so named for the handles that came above the top of the vessel. Mycenaean vessels usually had a pale, off-white background and were painted in a single color, either red, brown, or black.

Popular motifs include abstract geometric designs, animals, marine life, or narrative scenes. The presence of nature scenes, especially of marine life and of bulls, seems to suggest a Minoan influence on the style and motifs painted on the Mycenaean pots.

Vessels served the purposes of storage, processing, and transfer. There are a few different classes of pottery, generally separated into two main sections: utilitarian and elite.

- Utilitarian pottery is sometimes decorated, made for functional domestic use, and constitutes the bulk of the pottery made.

- Elite pottery is finely made and elaborately decorated with great regard for detail. This form of pottery is generally made for holding precious liquids and for decoration.

Stirrup Jars

Stirrup jars, mainly used for storing liquids such as oil and wine, could have been economically valuable in Mycenaean households. The arrangement of common features suggests that a stopper is used to secure the contents and the contents are what make the jar a valuable household item.

The disc holes and third handle may have been used to secure a tag to the vessel, suggesting it had commercial importance and resale value . The locations where stirrup jars have been found reflect the fact that the popularity of this vessel type spread quickly throughout the Aegean, and the use of the stirrup jar to identify a specific commodity became important.

Warrior Vase

The Warrior Vase (c. 1200 BCE) is a bell krater that depicts a woman bidding farewell to a group of warriors. The scene is simple and lacks a background.

The men all carry round shields and spears and wear helmets. Attached to their spears are knapsacks, which suggest that they must travel long distances to battle. On one side, the soldiers wear helmets ornamented with horns. The soldiers on the other side wear hedgehog-style helmets. A single woman stands to the left with her arm raised and a group of identically dressed and heavily armed men is marching off to the right.

There is no way to tell which woman is waving goodbye, as all the figures are generic and none specifically interacts with her, nor do they interact with each other. The figures are stocky and lack the sinuous lines of the painted Minoan figures.

Furthermore, while the men all face right with wide stances and appear to move in that direction, their flat feet and twisted perspective bodies inhibit any potential for movement. Instead the figures remain static and upright. The imagery depicts a simple narrative that in the warrior culture of the Mycenaeans must have often been reenacted.

Many scholars observe that the style of the figures and the handles of this thirteenth century BCE vase are very similar to eighth century BCE pottery. Similar spearmen are also depicted in eighth century BCE pottery which introduces a curious 500 year gap in styles.

Other sculpture

There are few examples of large-scale, freestanding sculptures from the Mycenaeans. A painted plaster head of a female—perhaps depicting a priestess, goddess, or sphinx —is one of the few examples of large-scale sculpture.

The head is painted white, suggesting that it depicts a female. A red band wraps around her head with bits of hair underneath. The eyes and eyebrows are outlined in blue, the lips are red, and red circles surrounded by small red dots are on her checks and chin.

the story of an artwork's discovery, findspot, and its various owners through history

restoration generally involves returning a site (or objects) to an earlier state, often through the use of non-original material. Ideally, all added material is detectable and treatments are reversible.

a scientific discipline that seeks to preserve cultural heritage for the future and can involve cleaning and repairing--ideally repairs are visible, but not distracting to the viewer.

Sir Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who first uncovered the palace at Knossos, divided Minoan chronology into many different periods with distinct abbreviations. LM II stands for the second part of the Late Minoan period.

in true, or buon, fresco, pigments are applied to wet plaster and the resulting painting becomes part of the wall itself, with vivid and well-preserved colors. In fresco secco, wet pigments are applied to already dry plaster.

stone coffin, from the Greek word for limestone ("sarkophagos"), from sark (flesh) + phage (eat)

a drink, generally one poured out as an offering to a deity

mythical element that combines the physical aspects of a lion and eagle

a type of ceramic with a glass-like surface

Sir Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who first uncovered the palace at Knossos, divided Minoan chronology into many different periods, including the Neoplatial period, sometimes abbreviated as MM III.

an architectural technique in which material is built up in successive layers, or courses, with each one overhanging the one below it until they meet in the middle at the top

a rectangular hall, fronted by an open, two-columned porch. It contained a more or less central open hearth, which was vented though an oculus in the roof above it and surrounded by four columns. The architectural plan of the megaron became the basic shape of Greek temples, demonstrating the cultural shift as the gods of ancient Greece took the place of the Mycenaean rulers.

a circular tomb of beehive shape approached by a horizontal passage in the side of a hill [Merriam-Webster]

a row of evenly-placed columns

a metalworking technique in which the decoration is hammered into relief from the back of a thin sheet of metal. From the French "pousser," to push.

sculpture that, unlike free-standing or in-the-round sculpture, doesn't detach entirely from its background. High-relief sculpture projects far from the background, whereas low-relief, or bas-relief sculpture is relatively shallow.

a ritual vessel used for pouring liquids, often in the form of an animal or animal's head

large, open-mouthed vessel for mixing water and wine